Trending

Current Read

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

Teler Sishi Bhanglo Bole Khukur Opor Rag Koro

Tomra Je Shob Buro Khoka Bharot Bhenge Bhag Koro! Tar Bela?a

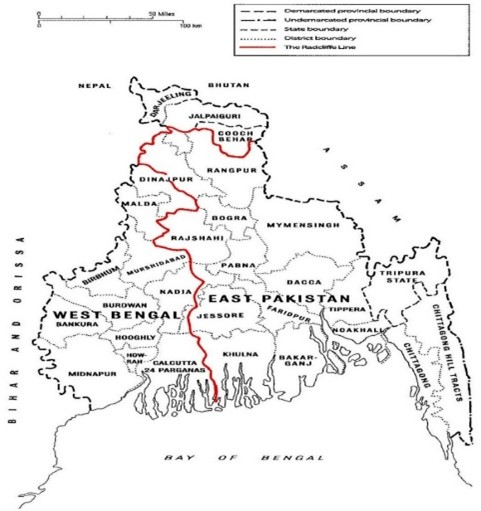

The partition of 1947 consists of a significant phase in the Indian historical discourse. As depicted in the lines of the famous Bengali poet Annadashankar Ray, it stands as one of the most traumatic events of the past century. The end of the colonial rule was characterised by the creation of two independent domains – of India and Pakistan. A pinnacle culmination to the ‘divide and rule’ by British, the breakage had a long rippling effect.

The partition flagged one of the biggest migrations in history. Especially in Bengal, there are innumerable stories of resistance, struggle and a desperate fight for identity. The pandora’s box has a lot within it. As millions packed bag, our current piece would essence on such an aspect.

I’ve grown up in the city fringes of Netajinagar. A neighbourhood in South Kolkata, there stands a sculpture in a four-way crossing point. Since childhood this encapsulates me a lot. The frame bears three striding figures clutching possessions. A family torn by mishaps, one of them carries a child on a shoulder to way full of uncertain bents. Bastur tagide srishtir karigor, tomaderi srishti ajker ei nogor (Compelled to create a home you became the creators of today’s city) – these are the words written in their honour on a plaque below. Every year on 26th January the people of Netajinagar celebrates the inception of the colony. Netajinagar turned 75 this year.

Being a third-generation diaspora, I’ve always tried to connect myself with the wounds of past. The strains my grandparents faced. The pain of leaving behind their home and roots. The village they once called their ‘homeland’, the yard where they spend their entire lives, no longer belonged to them. They packed the meagre belongings and embarked on a challenging journey towards an unknown.

The Radcliffe line mercilessly ripped through heart. The sudden stroke of ’47 on the map caused a desperate migration of people. As the communal tension grew rapidly in areas, millions fled across borders. Unlike Punjab, things were quite different in Bengal. While influx was for once in former, it has been a recurrent theme in the latter case. The refugee issue sparked a lot of tensions in Bengal. As per statistics, between the years of 1946 and 1958 almost 31 to 32 million people sought refuge in West Bengal. In 1961, over 18% of Kolkata’s population were migrant refugees. Referred to as Udbastu in Bengali, the city got packed with them. As contemplated by researchers, managing the overwhelming numbers became a massive challenge for the nascent state and nation. The migrants faced a lot of hitches in re-establishing a life. Especially for the middle class and lower, rehabilitation became a prime concern.

The refugees were initially stationed in Shealdah. While many took a shade in parks or abandoned buildings, life in camps was more than pathetic. They lacked space. Same goes in case of logistics as well. Undermining the basic of even privacy, questions like health and hygene were seriously sapped. One shall mention of a report in this regard. Entitled ‘East is East: West is West’ (1955) it exposes the misery in the camps. There was absolutely no concern for hygene. Malnutrition being common, diseases like cholera, diarrhea and dysentery were rampant.

The permanent rehabilitation process was slow and tedious. Being pushed for days, the refugees now took over each available space in and around the towns. They occupied every vacant land overnight. From pavement to sidewalk, this included – runaway of airfields, railway tracks, allied military barracks and even the scrubland and unsanitary fringes of the sewage drains.

The illegal occupation often led to cases of turmoil. As documented in time, there were occurrence of serious clashes between the people and the police. The city lacked the basic of intent. So was the issue with management. Unable to rightly accommodate the ones, the State Government ignored the circumstances and rather favoured the landowner’s property right.

Around 389 camps were functional in several parts of West Bengal. Among them Kolkata had four major ones in Ghusuri, Kashipur, Ultadanga and Disparate living conditions of these camps were inhumane. Poor sanitation led to the death of thousands. Coupled with corruption and hoarding by officials, this graved the situation even more. From the ’50s, the refugees started taking the matter in their own hands. Group of men assembled and formed Dals. This was based on either family relationship or former connections from East Bengal.

One of the prime tasks of the groups was to track a land. Once a proper piece of land was located, they followed a significant pattern. They thoroughly measured, divided it and gave out individual plots to each refugee family. The squatters had to build a thatched shelter overnight. By the time authorities showed up, it was already a fully grown settlement. This form of land encroachment was known as ‘Jabar Dakhal’ or ‘squatter colony’. Springing along the deserted barracks or railway tracks, the city got dotted with it. However, there were also Government allocated properties, referred as – hukum dakhals. These lands were mainly for those who could afford it.

By 1967, Kolkata and its adjacent had 756 squatter plots, while the government sponsored colonies were 503. The northern zone of the city contained 60 to 80 colonies, the north-east area had 50 to 70. However, the southern part of the city ranged the most. Boasting around 80 to 100, some of the prominent colonies of South Kolkata included – Jadavpur, Bagha Jatin, Bijoygarh, Azadgarh, Arabinda Pally and Netaji Nagar – all named after significant personas. A way of legitimacy, this equipped the Udbastus with a sense of an identity.

The Bijoygarh colony was one of the earliest squatter colonies of West Bengal. Initially it was Jadavpur Bastuhara Samiti. In 1948, it started with 12 refugee families and one abandoned military barrack. Basanti Devi, the wife of late Chittaranjan Das, contributed significantly to the development. As a president of Jadavpur Refugee Camp Association she, along with Santosh Dutta, played a crucial role in its shaping. The area was under a local influential landlord. Infamous for his notoriety, he hired goons in 1949 to wash off the already settled refugees. However, the udbastus stood tall. Putting a stiff resistance to the face, they fought, won and the area got renamed as Bijoygarh or the Fort of Victory.

In 1950, similar happenings occurred at another place in Tollygunge. Under the leadership of Indu Ganguly, a group of refugees occupied another vacant land. After noticing an untended zone for days, Ganguly approached the owner to give them the land on lease. However, after the owner refused their proposal, the refugees forcefully occupied the land, divided and distributed it within others. The new colony was named- Azadgarh meaning Fort of Freedom.

Thus, much like that of Bijoygarh or Azadgarh, each rehabilitation has a story of its own. The colonies advocated self-management practices. They vouched for democratic decision-making process. In order to maintain the zone, Dakshin Kolkata Sahartali Bastuhara Samiti was established in 1950. They emphasised on education and socio-cultural advancement. Furthermore, focusing on community build-up initiatives such as brick-lined roads, pit latrines, tube wells, bamboo bridges, playground for kids including health centres, school, colleges and library were taken. The Azadgarh Balika Vidyalay was inaugurated in 1950. In 1951, the Netajinagar Balika Vidyamandir was founded. According to an identity and growth, all these thus paved the path for development of these masses.

Ushasi has completed her master’s degree in history from Calcutta University. Having deep fascination for the past, her idle goes by knitting history, clicking photos and exploring the unknown.