Trending

Current Read

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

“The qualities associated with it (the Mother archetype) are maternal solicitude and sympathy; the magic authority of the female; the wisdom and spiritual exaltation that transcend reason; any helpful instinct or impulse; all that is benign, all that cherishes and sustains, that fosters growth and fertility. The place of magic transformation and rebirth, together with the underworld and its inhabitants, are presided over by the mother. On the negative side the mother archetype may connote anything secret, hidden, dark; the abyss, the world of the dead, anything that devours, seduces, and poisons, that is terrifying and inescapable like fate.”

(The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious – C. G. Jung)

Bimal met Jagaddal the same year that his mother died and then on, Jagaddal is his only companion, the one who feeds him, cares for him and likewise Bimal does the same for Jagaddal. Jagaddal is the only thing in his life that he cannot compromise on, not even when it comes down to his stomach. Jagaddal is his car.

More or less all of us, at least the ones who have studied in Bengali schools in Bengal have read Subodh Ghosh’s “Ajantrik”. One recalls the feeling of awe and wonder when one read it for the first time. Upon revisiting, a pang also accompanies this feeling; children too, quite often attach themselves with inanimate objects which inevitably break. In Ghatak’s own words – “…it is a silly story. Only silly people can identify themselves with a man who believes that God-forsaken car has life. Silly people like children, simple folk like peasants, animists like tribals.” (It comes as no surprise that the last scene shows Bimal watching a child and reminiscing)

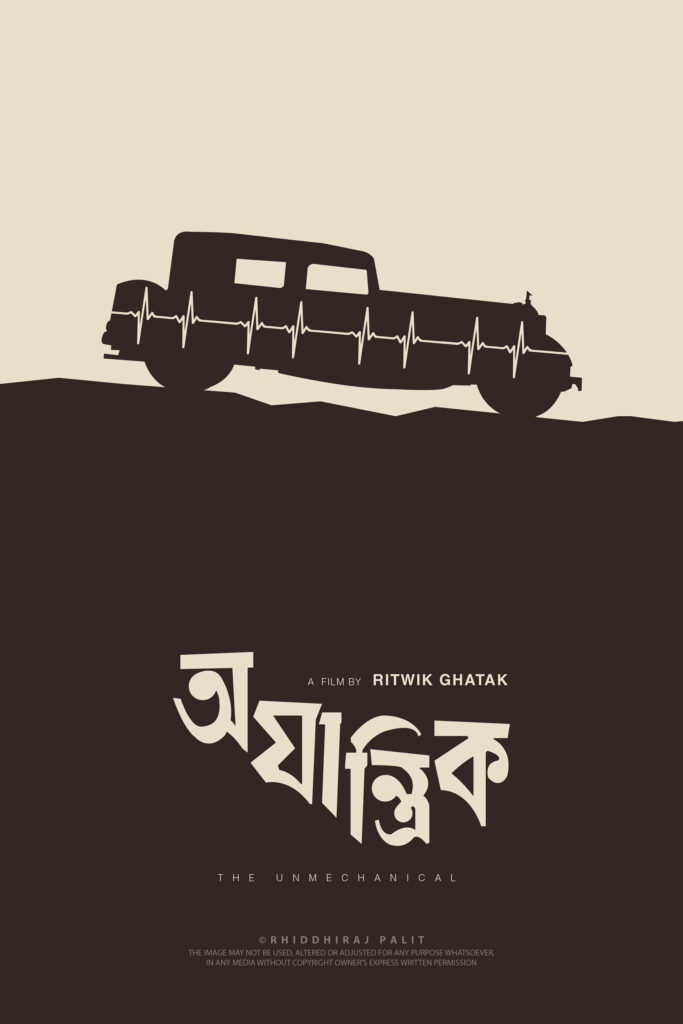

However, Ghatak turns this “silly story” into a Cinema with a beating heart and that too quiet literally. One comes across the dance of the Oraon tribe, their musical beats resembling the systole and diastole of the heart. Jagaddal too is turned into a person not just for Bimal but for the audience as well, made apparent by sounds and gestures that of its horn, headlights etc. Bimal and Jagaddal are in tune – when one feels hurt, the other understands and when in pleasure the other responds. Man’s love with the machine is more relevant today in this technocratic age of loneliness. AI today is a friend too. It is much easier to imbue soul into the material and create the Other rather than reach the Other. Also, the dialogue with this Other is more of an introspection than conversation. When Bimal leans against Jagaddal and speaks with him or, when he congratulates him for completing a trip on time – that’s the time when Ghatak lets the audience peek into his psyche.

Coming back to the reason for starting this essay with a Carl Jung quote, Ghatak himself says “…all art is subjective. Any work of art is the artist’s subjective approximation of the reality around him.” Thus, it is inevitable that this subjective approximation carries itself forward to the audience too. The audience tries to encase the art into the confines of their own mind and create an amalgamation in the process of art experience. Revisiting Ajantrik felt like that experience – it might be one’s own stereotyped mind where one attaches everything to human relationships or one’s own personal psyche which interprets the movie in its own way. Or rather it can be the Collective Unconscious which presents itself in differing images in different ages.

Jagaddal becomes the Mother to Bimal. He becomes the only place of comfort for Bimal, the only thing Bimal trusts in this barren land where survival of the fittest thrives. He gets enraged when the mechanic denigrates Jagaddal as something less than his mother, something not worth fighting for; becomes frustrated when Jagaddal doesn’t support his endeavor to connect with a suitable female companion. A feeling of betrayal engulfs him when Jagaddal becomes sick (broken) as a result due to his endeavor. Bimal, feels like a child, a child who hurt his mother unknowingly. He gives his everything to make Jagaddal healthy again. He is not like that lunatic who forgets his old pot for a new shiny one. Though he lives near a cemetery, he is not the one to mourn the dead. But, when Jagaddal becomes healthy, Bimal fails to find his old Mother in him. He simply can’t accept this new ship of Theseus – the sound has changed – the Mother has changed. Thus, he does the only thing he can think of. In a desperate act of bringing back his Mother, he kills her.

Ghatak not only adapts Subodh Ghosh’s story, he makes it much more sinister and real. To top it off, he does this without any dialogue. From the sound of his heartbeats laid in the tribal dance to the screeching sound of his death, from his thirst as the radiator gulps down water to his metal clanging deathbed as the scraps are taken in the van every detail etches life into Jagaddal.

The Oraon tribe here adds more subtext to the story in Ghatak’s own words – “They are constantly in the process of assimilating anything new that comes their way … the tribe I chose—the Oraons—are very culture-minded and have this tendency in a pronounced manner.” Ghatak said these words for the love of the machine but the portrayal of Oraons can be interpreted as antagonistic with respect to Bimal. In the last stage of the movie, when Bimal is still trying to revive Jagaddal, an Oraon woman is seen grieving by the cemetery, thereby giving into a process of assimilation which Bimal fails to do. One cannot always stay in their Mother’s shadow as change is inevitable. Bimal’s journey is therefore towards that of the Oraon of whom he was initially polar opposite. Bimal does finally shed the tear upon seeing a little boy playing with the scraps of a car, his once beloved Jagaddal.

Alas, there’s no way to confirm if Ghatak intended Ajantrik to be interpreted as an oedipal saga but that is what defined him as an artist. One who not only shows what he feels and thinks but one who saves space for the audience to experience and express.

Hrithik Upadhyay is a lifelong philosophy student and film enthusiast. While his accidental collision with engineering and AI training earns him his bread, one can mostly find him either running errands on random film and theatre sets, or in a heated debate with friends or-as recluse, in the most remote villages, teaching children.