Trending

Current Read

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

Minoti hated her name. So old fashioned and back dated. Her annoyance with her parents for not having a spine to stand up to her grandparents when they named her so. ‘A prayer or was it supplication?’ The servility of her name riled her. Almost as if at birth it was decided that she would not be the master of her destiny. She would pray or beseech others to allow her, her space.

‘I guess, I am having a bad phase,’ Minoti ruefully thought. ‘It is all Manas’ fault. He wanted me to take a quick decision about the house. As if one can decide in a moment what to do with one’s ancestral house in a trice!’ Minoti grumbled as she rummaged through her bag for the set of keys to open the door of the house. ‘When had it ceased to be a home, I wonder,’ she thought.

Warm, musty, locked in air greeted her in a strange welcome. ‘That good-for-nothing Barun, taking thousands every month and this is how the state of the house is?’ It seemed like time has come to a standstill in that house. The corridor, with its black and white mosaic tiles looked exactly the way they did when Minoti, Abheri, Monisha and Jagannath played ‘ekka-dokka’ there. ‘Strange, why did I remember the proper names of Duli, Moni and Babu?’ She was as close to her cousins as one was to one’s own brothers and sisters. Growing up in a joint family, one did not even understand the distinction between own siblings and cousins. Those things were unheard of in those days. Turning the corner she saw the rows of rooms with interconnecting doors through which the children rushed around playing tag and being yelled at. ‘Those were the days, not a care in the world!’ Minoti sighed inwardly. ‘Life is so hectic nowadays. I always feel like there is so much to do and so little time.’

Beyond the rooms lay the large kitchen. Peeping in, Minoti saw the inroads of modernity by way of the gas oven but beyond that lay the huge ‘unun’, a large clay oven which was fed by coal and wood and from where her mother, jethima and kakimas produced ambrosial culinary delicacies. ‘Even food tasted better then,’ she thought and then grinned at her soppy, sentimental musings.

Unknowingly her feet took her up the stairs towards Thammi’s room. Her paternal grandmother was a force to reckon with. The matriarch of the Gangopadhyay family, she ran a tight ship. Minoti had never really warmed up to the lady and vice versa. Everything seemed just as it had been except for a layer of dust that glistened as she opened the window overlooking the garden. Her ancestors had bought the land, a large tract of it in the heart of the old city in Bhowanipore and with much care and grandeur produced this rambling mansion that was once upon a time, chockablock filled with close and protracted family members.

For the first time, Minoti noticed the silence. So strange, she did not remember the house ever being silent. There was always, always something going on. Today it felt strange, almost as if the house wanted, waited to hear from her. She climbed up further to go to the terrace, a forbidden zone for the children unless accompanied by elders. How they had craved to explore the nook and crannies of that forbidden world and been resoundingly chastised for trying, each time. In a child’s mind, the forbidden exercises a hypnotic pull. Minoti and her cousins were no exceptions.

Minoti’s measured footfalls echoed on the large terrace. The dust danced with every step. The combination of the breeze and the almost setting sun was bracing. Minoti felt strangely rested. She would have to sell off the house as the sole survivor of the Ganguli clan. The promoters were vulturing and so were the Party dalals. Manas was an ordinary mortal unable to fob of any of them. He was pressurising Minoti to take a stance. Not that Minoti herself did not want to take a decision. She had made up her mind to sell the house to Bajoria Ji. He was offering her an insane, obscene amount of money for the property. He wanted to make a shopping mall there, prime location he said. The allure of the money was too much. All her life, she had wanted to do things – travel, read, cook at leisure which of course required money to execute. Now finally, she was going to have a chance to do all that.

On the northern side of the terrace there used to be an orchard of the best Totapuli mangoes that her uncle had painstakingly planted. The smell of the mangoes at fruition was something that Minoti remembered with relish. Now, the garden lay in disarray. Weeds had taken over and were having a field day.

“Ei Minooooooo!” The cry rented the air. It has been years since she had heard someone call her that. Surprised, she tried to figure out where the call had come from. “Ei Minooooo,” once again it was heard. It sounded so familiar. She rattled her brains to recognise the voice. ‘Duli!’ She was startled. Her best friend and cousin. Her only confidante in the foreboding house. Minoti’s gaze travelled the length and breadth of the terrace and the garden below. She seemed to spot the polka-dotted dress of her cousin. She craned her neck to see clearly.

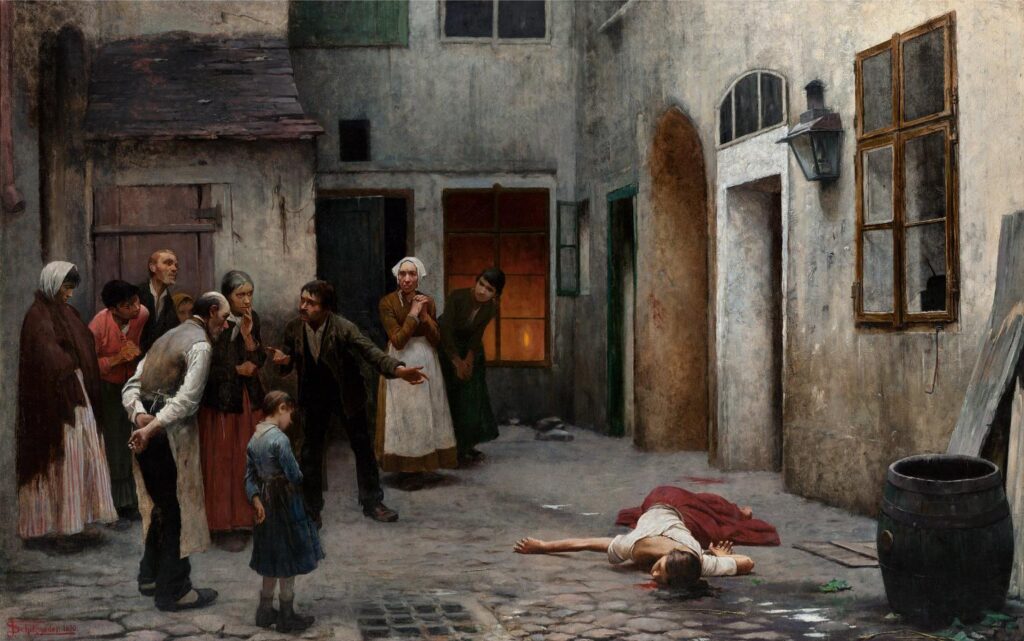

‘Why is Manas creating such a scene?’ Minoti wondered. “Ei Minooooo, aay, aay, chol kumir danga kheli,” Duli called out to her. “Chol!” Said Minoo. She turned back, looked upwards towards the terrace to see a frantic Manas with others she did not recognise. They were pointing downwards. An oddly familiar-looking lady in a yellow sari lay spreadeagled on the garden floor. Her arms flung out as if she had been trying to grasp something. Manas looked strange, grown up, unknown. Not the naughty boy he was from the next house in their locality.

“She fell, perhaps,” the police officer said. “But we cannot rule out foul play,” he said. “There’s a lot of money involved, Mr. Chatterjee. You will have to come to the police station with us. We need your statement.” A tuft of yellow material, a piece of Minoti’s sari, fluttered in the gentle breeze where it had caught the rusty nail when she fell.

Ruma Chakraborty is a senior English faculty in a premier institution in Kolkata. Teaching is both a profession and a vocation for Ms. Chakraborty. It is but one of the hats donned by her. A painter, a budding poet and compulsive storyteller, currently she is in the process of writing a compendium of short stories and poems.

An alumna of Loreto School, St. Xavier’s College and Calcutta University, an intrepid traveller; a typical ‘Bangali’ in matters of food; an example of the argumentative Indian; an inquisitive learner to boot—she is a quintessential Renaissance woman.