Trending

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

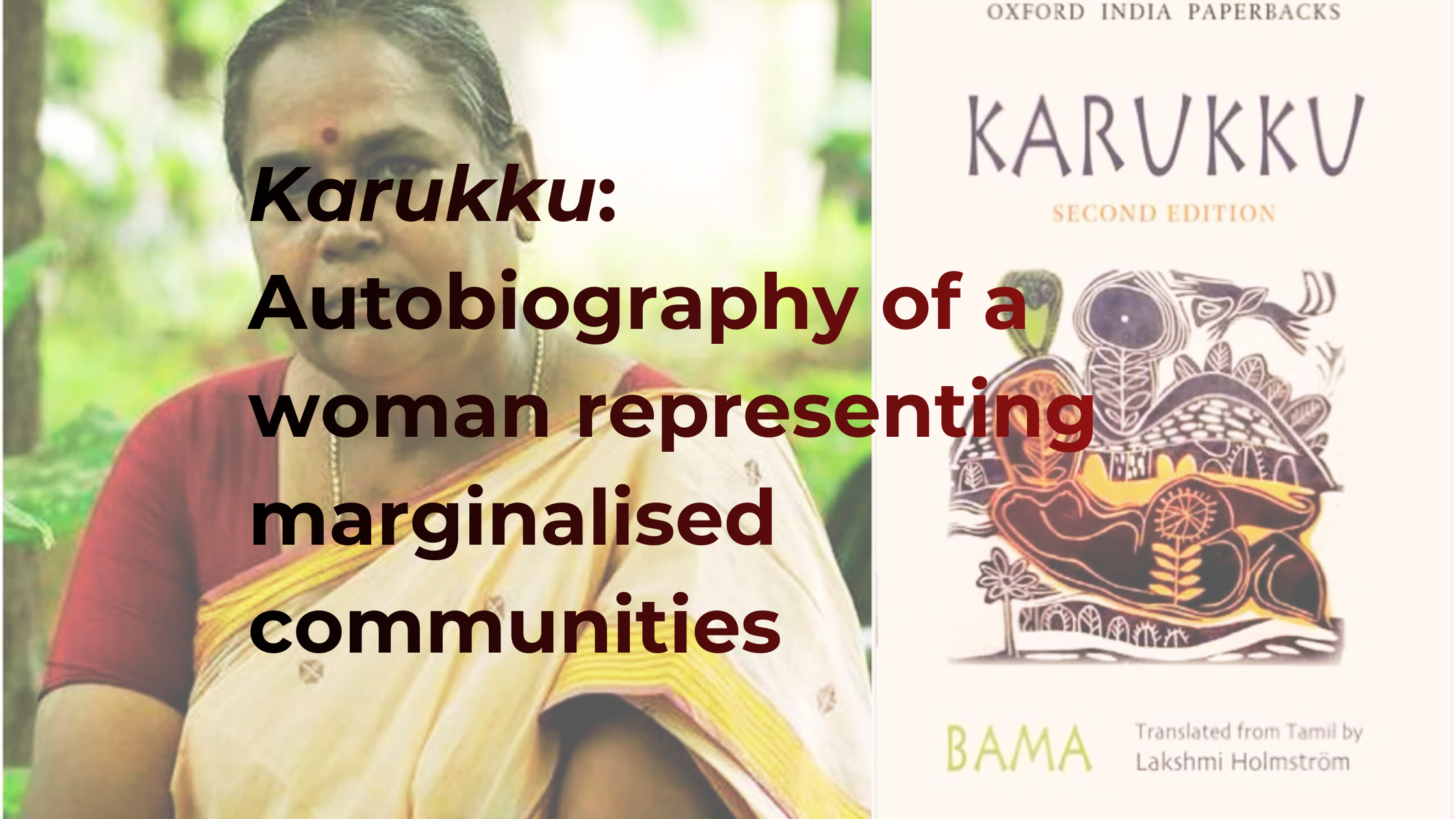

Bama Faustina Soosairaj begins her discourse about her life and struggles in an unusual manner; the first few passages of her autobiography, Karukku, describe the beautiful mountains that surround her village. Karukku, published in 1992, is considered to be the first Dalit autobiography written in Tamil by a low-caste Christian woman from a small village in a remote corner of Tamil Nadu, focusing on her experiences with caste oppression. Naturally, a reader will not expect a description of nature at the very onset, and this is where Bama is successful in catching us off guard. While talking about mountains, she mentions the upper caste Naicker community and the Perumal Saami Temple, which is only reserved for them as a place of worship; she introduces caste discrimination and oppression in a highly innocent and cunning manner. The author does not narrate her story in a linear pattern, but rather in a confessional tone, recollecting anecdotes from her past; we are continuously taken back and forth between periods from her childhood and adult life. She is not entirely dependent on experiences, either; we find her providing extensive commentary on her opinions about the conditions of her surroundings and her ideas of social reform. Her autobiography focuses on two aspects of her life: firstly, her life as a Dalit woman, and secondly, her experience with the Church and the convent, which she initially views as a place of salvation and emancipation, but is eventually disappointed and disillusioned with. She documents her lived experiences, a potent method of protest against social injustice and corruption, challenging an exploitative social order. She deals with her individual frustration and predicament as a Dalit Christian but also talks about the collective experience of an entirely marginalized subaltern community of India, the Dalits, microcosmically revealing the rigidity of the age-old Varna system that has been internalised in the Indian masses and is still practiced intensely in rural areas and small towns.

The title Karukku means palmyra leaves in Tamil, which have sharp blades on either side, like double-edged swords. Critics have interpreted this imagery in two ways: the sharpness of the leaves denotes the wounds of humiliation inflicted by centuries of oppression, but the same sharpness represents a potential weapon that will cut through the vicious cycle of atrocities (Singh, p. 106). This autobiography is a seminal work in the Dalit literary canon, as it explores a postmodernist intersectional perspective on subaltern identities. Bama is not seen as a human being worthy of living a good life; she is seen through different lenses, but never the right one. She is a Dalit, a Christian, a Tamil, a woman, but never as a fellow individual; it is this lost sense of individuality she wants to reclaim through her autobiography and is successful in her endeavour. Bama’s grandmother underlines the mass mentality of the Dalit community when talking about the master slave relationship between the Parayas, which is her own caste and the Naickers (Bama, p.17). She says, “These people are the maharajas who feed us our rice. Without them, how will we survive? Haven’t they been upper caste from generation to generation, and haven’t we been lower caste? Can we change this?” At a later point, the author herself admits to following the oppressive rules put in place by the Naickers because she cannot revolt against these wealthy people. She is always angry and frustrated with the state of affairs and yet she is unable to protest because her socio-economic position is much inferior to them. She talks about how her elder brother is respected despite being a Dalit because he is highly educated and his strong educational background gives him an upper hand when dealing with the Naickers. This inspires Bama to pursue an academic career, despite her parents’ financial limitations and their greater concern for her marriage, as they hold the absurd notion that education is only beneficial for men. Bama also talks about the intense rivalry and hatred between different sections of the Dalit community, stating that the Naickers are in a dominating position because they can capitalise on this lack of unity and continue the vicious circle of exploitation. Only once, we may observe that Bama is biased in her description of the conflict between the Parayas and the Chaaliyars, where she portrays the people of her caste as completely innocent and helpless, which might not be the case, as the rivals here are also low caste people.

Bama, like a large section of Dalit people, comes from a family of converted Christians. This tradition of low caste people converting to another religion to escape the Varna system in their own religion comes as a part of India’s history as a former colony of European countries. Bama is inspired by the teachings of the Holy Scriptures and the figures of God and Jesus initially. Still, it is strongly opposed to the Church and convent schools. She believes that these institutions are just another place of discrimination. The missionaries are never concerned about the upliftment of the poor and emancipation of the oppressed; they are focused on increasing their religious clout by converting poor Dalits to use them as manual labour in the service of rich Christians, who are given essential positions of administration. It is astonishing to observe that organizations that advocate a life of poverty and sacrifice in the name of a holy cause can be involved in oppression of a different kind. Bama notes that the nuns share the same beliefs as the Naickers when it comes to Dalits, deeming them as dirty and inferior to the rich employees and students, and fit for menial jobs like cleaning toilets and maintenance work. Bama becomes a maths teacher and eventually a nun due to her good education. Still, she is disillusioned with the convent and is subjected to humiliation. At first, as a student, she is isolated by her classmates and teachers, and later on, the nuns are prejudiced against her for being a Tamil and do not want her to be promoted in her job because of this. Bama observes that the nuns lead a comfortable life at the expense of the donations meant for the underprivileged; she even says that the nuns fall upon the poor people like ‘rabid dogs’ instead of helping them. She is afraid when she tries to leave the convent, as the authorities are desperate to keep her in, out of fear of being exposed. However, she manages to free herself at last, and that is where she ends her autobiography. Professor Pramod K. Nayar calls Bama’s account a ‘testimonio,’ which is true. Still, she also represents different subaltern groups present in society. When discussing social reforms necessary for women’s empowerment and the proper functioning of social and religious institutions, Bama is often repetitive because she lacks great literary ability; however, her arguments are highly potent and grounded in real-world realities. In the end, Bama reflects on the future after she has left her job at the convent and is returning to her village. She knows that the men in her life will pass judgment on her choices but not help her start afresh. As a woman, it will be a great challenge for her to establish herself while fighting against the firmly embedded notions of patriarchy. She says at one point, “I will survive” when she is finally able to embrace her religious, regional, gender, and caste identities proudly and compels society to recognise her as a human being who deserves equal rights and opportunities, and most importantly as a competent and talented individual.

Rishav Nayak is an aspiring writer from Kolkata, West Bengal, India. He has completed his Bachelors in English from the Bhawanipur Education Society College (affiliated to CU) and is currently pursuing his Masters in English Language and Literature from University of Calcutta Central Campus. His research interests are Popular Culture, Folklore and Mythic Anthropology, Films, and Socio-Political Discourse. He is also actively involved in amateur theatre for many years and is also an avid quizzer, along with being a voracious reader, melophile, and cinema aficionado.